Suicide Prevention Month, which takes place every September, draws global attention to a silent crisis that ongoingly claims the lives of people of every age, families, and communities. Nearly 720,000 people taking their lives each year and countless more attempting to do so, suicide is the third learning cause of death among 15 to 29 year olds (WHO, 2025). In 2019, there were 2.5 suicides for every 100,000 people in the Philippines (Department of Health, 2019). More recently, almost 2,000 deaths by suicide were recorded by the Philippine National Police in the first half of 2025. (Clapano & Tupas, 2025). Together, the statistics listed point to the critical need for immediate action and preventive measures, with suicide remaining a pressing public health concern.

Barriers to suicide prevention

Why prevention remains difficult, despite having such measures to address it, lies in a number of reasons for delaying assistance to those at risk, from societal attitudes to structural challenges in accessing care.

1.) Social stigma of suicide

Some of the most prominent barriers to Filipinos seeking help are stigmatized views on mental health conditions. According to recent local research by Bollettino et al. (2023), beyond financial limitations, the top reasons Filipinos do not seek mental health care are emotions of shame or humiliation, fear of being viewed as “weak” or “crazy,” and concern about the reactions of family members or others. These deeply ingrained cultural beliefs raise the possibility that the risk of crises may go unreported, therefore contributing to silence and delay in seeking assistance.

2.) Lack of access to mental health services

As reported by the United Nations Development Programme (2021), there is a critical shortage of mental health service providers. For more than 100 million people, there are only about 548 psychiatrists (0.5 per 100,000 people), 516 psychiatric nurses (0.5 per 100,000), and 133 psychologists (0.1 per 100,000). Access to services remains highly uneven; most specialists are in Metro Manila, leaving nearly all areas rural and remote with little to no access to mental health care. This also holds for infrastructure; the entire country has only four mental health hospitals, 58 custodial or residential private psychiatric facilities, and 29 outpatient mental health facilities with a bed ratio of only 94 per 100,000 population. Additionally, about 65% of such hospitals are already owned by the private sector accredited by the Department of Health, which further limits accessibility for low-income populations.

The high costs of such services also presents another barrier for many people. In Metro Manila, psychiatric consultations cost between ₱500 and ₱4,500 each session, while psychological consultations cost between ₱1,000 and ₱3,000 (Dahildahil, 2023). In addition to the medication costs averaging at about ₱50 to ₱100 per pill, this would make it burdensome to many Filipinos who would be maintaining the treatment.

Importance of community in mental health

Given this mental health gap, it is crucial to strengthen social support for persons impacted by suicide. The community provides that support through several ways.

1.) Social support is protective

The psychological and emotional benefits to individuals can be found when one is a part of a supportive community, given that close social connections offer emotional support, practical help, and a sense of belonging which serve as a buffer against stress, worry, and depression. This is made evident by a 2024 study of Filipino adults that found that support from family, friends, and significant others significantly reduced stress and, in turn, lowered symptoms of anxiety and depression (Acoba et al., 2024), therefore community remains as a protective factor for mental wellbeing.

2.) Access and cultural relevance

Inequitable access to mental health care has been a recurring problem for decades, particularly in underserved populations. In order to address this, community engagement strategies have surfaced, providing essential mental health services in the comfortable and customized contexts of people’s social and cultural surroundings. For example, the Davao Center for Development (DCHD) established Community-Based Mental Health Programs (CBMHPs) and implemented the WHO mhGAP-IG, including a pilot Schizophrenia Project across four municipalities (Matalam & Hembra, 2022). The program improved patient outcomes, reduced hospitalizations, and increased service utilization, while also highlighting challenges like project implementation and transportation barriers. Given its importance, there should be prioritization of the establishment of community-based mental health services, and processes to improve mental healthcare accessibility and affordability (Alibudbud, 2023).

3.) Community engagement strengthens networks

Whereas personal relationships are important, community engagement goes one step further by actively establishing and maintaining networks of care. Rather than depending on the available social relationships alone, communities can set up programs to link individuals, promote mutual support, and provide safe space for healing and sharing. A good case in point is a community-oriented intervention in Filipino older adults that demonstrated the impact of peer counseling and organized social activities on significant improvement in depressive symptoms and psychological resilience (Carandang et al., 2020). Such efforts illustrate how purposeful community action can extend the scope of care outside individual networks, enhancing early detection, making referrals easier, and interweaving extended networks of care that reach even those who would otherwise be left behind.

4.) Stigma reduction through community

Initiatives run by the community have been essential in lowering the stigma associated with mental health. One excellent illustration is #UsapTayo, a MentalHealthPH online campaign that promotes candid discussions about mental health and normalizes asking for assistance (Zuniga et al., 2020). Taliana (2023) quoted that many Filipinos opt to delay receiving care because of the stigma surrounding their mental illness, embarrassment or shame of discussing it. Through active dialogue within the community, it transforms the then stigmatized mental health problems into shifting the narrative from fear towards empathy and acceptance. Activities such as peer-led gatherings, anti-stigma campaigns, and sharing personal stories will help people relate and normalize mental health issues through them. All these initiatives create safe spaces and teach in culturally relatable ways so that mental health becomes easier to talk about and available for all.

Building a Suicide Prevention Strategy

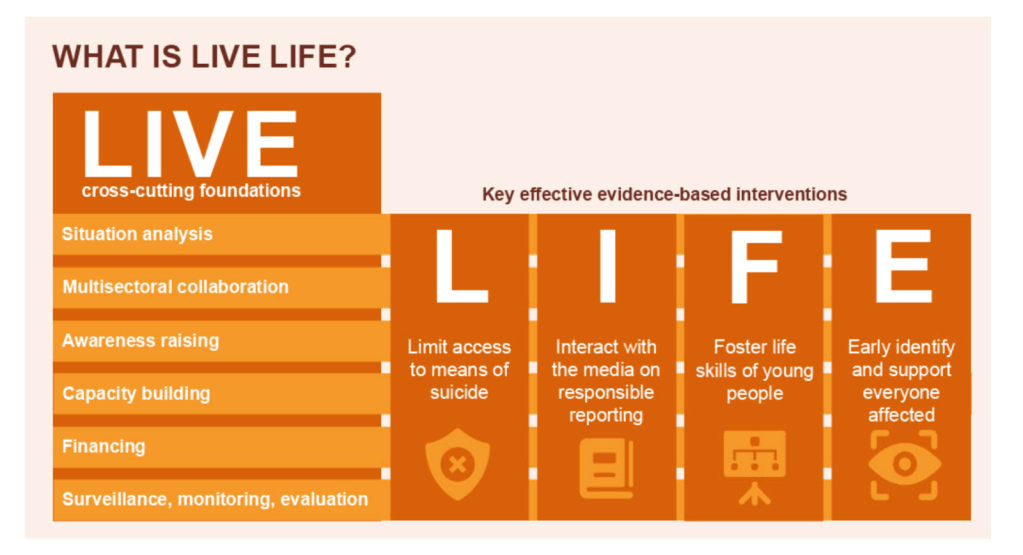

Suicide should be treated as a serious public health issue, requiring action from all sectors and levels of society. The World Health Organization (2021) recommends a holistic approach to suicide prevention using the LIVE LIFE Initiative.

The LIVE cross-cutting foundations include six pillars for suicide prevention, which supports four evidence-based interventions under the acronym L.I.F.E. This model serves as a guide for developing the country’s national suicide prevention strategy.

- Situation analysis

A situation analysis provides background to the present profile of suicide and suicide prevention in the country, either at the national, regional, or local level. This should be the first step in planning any intervention because it identifies areas of greatest need for suicide prevention initiatives.

- Multisectoral collaboration

Suicide is not just a mental health issue. Its causes can be traced to many interacting elements in society. According to Gallagher (2025), the top social determinants of suicide include:

- Housing, basic amenities and the environment

- Income and social protection

- Unemployment

- early childhood development

Therefore, suicide prevention requires a whole-of-society approach.

- Awareness raising

Organized campaigns can bring to public awareness key messages about suicide, such as where people can seek help or how one can support someone in crisis. Awareness raising strengthens a suicide prevention strategy by increasing political will to allocate resources towards suicide prevention, even among non-health sectors. In the public, it also changes stigmatizing attitudes towards suicide and encourages help-seeking behaviors.

- Capacity building

The successful implementation of a suicide prevention strategy depends on the knowledge and skills of people to deliver the LIVE LIFE initiatives. Training sessions should target key groups like mental health and primary care professionals, emergency service workers, and other persons working with high-risk groups like the youth, older adults, and persons deprived of liberty.

- Financing

Obtaining financial support for suicide prevention can be challenging due to limited resources and the lack of engagement from non-health sectors. LIVE LIFE implementers need to work around these problems by identifying potential funders from government and partner civil groups, developing strong proposals that emphasize the alignment of suicide prevention to the funders’ own goals and mission.

- Surveillance, monitoring, evaluation

Surveillance systems need to provide updated information on the prevalence of suicide and self-harm in the country to inform prevention strategies. Monitoring and evaluation collects information on the effectiveness, implementation, and cost-effectiveness of the LIVE LIFE interventions. The results can be used to scale up a suicide prevention strategy and mobilize support from government and community stakeholders.

These six pillars provide the foundation for the successful implementation of suicide prevention interventions. Four evidence-based interventions were outlined by the WHO, guided by the acronym L.I.F.E.

Limit access to means of suicide

- A suicide attempt may sometimes be an impulsive decision, unfortunately carried to completion due to access to lethal means like dangerous pesticides. Limiting the availability of these substances grants more time for a crisis to pass and for help to come.

Interact with the media on responsible reporting

- Media can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, sensationalizing cases of suicide can encourage vulnerable individuals to imitate the suicide attempt and contribute further to the stigmatization of suicide. On the other hand, responsible media coverage can promote help-seeking instead and mobilize support for persons contemplating suicide.

| Generally, how can people discuss suicide? Here are three areas to treat sensitively (Sinyor, n.d.): Be careful with the language: “Committed suicide” implies that suicide is a criminal activity. A more neutral alternative is “died by suicide.”A “failed/unsuccesful attempt” equates survival with failure. A better alternative is “attempted suicide.” (Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention, n.d.)Be careful with the graphics: Avoid graphic images that show suicide methods, stereotypical images of hopelessness, and identifiable persons impacted by suicide.Be careful with the message: Rather than depicting suicide as inevitable, highlight people’s ability to develop resilience and seek help. Direct people to suicide prevention experts and services. |

Foster socio-emotional life skills of young people

- Adolescence is a critical period for developing the socio-emotional skills needed to navigate everyday life. Schools, in partnership with the community and other organizations that deal with the youth, can conduct programs that target mental health literacy, problem-solving, and adaptive coping for stress.

Some community-based mental health programs for the youth:

Early identification and support for everyone affected

- Health systems need to educate health-care workers and even non-health community actors to identify warning signals, offer psychosocial support, and refer individuals to professional care.

- Clinical services are supplemented by crisis lines, community-based support, and survivor groups to provide accessible and culturally appropriate care for vulnerable individuals.

For more information on the LIVE LIFE model and its applications in different countries, visit: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/8f4bb596-e6e4-4328-a5ed-00e01ec0068d/content

How to identify and support someone at risk of suicide

A. Warning signs

Recognizing the signs of suicide allows one to provide help and be a source of hope for those in crisis.

1. Verbal Cues

They may talk about…

- Wanting to end their life

- “Gusto ko nalang mag-disappear.”

- Overwhelming guilt or shame

- “Wala na akong mukhang ihaharap sa kanila.”

- Thinking they are a burden to others

- “Ayoko maging burden sa pamilya ko.”

- Hopelessness about the future

- “Wala na akong pag-asa.”

2. Emotional cues

They may feel…

- Empty, trapped, or like life has no purpose with no reason to live

- Extremely sad, anxious, angry, or restless

- Overwhelmed by emotional or physical pain

3. Behavioral cues

They might…

- Make a suicide plan or research ways to end their life

- Distance from friends and family, saying goodbye, and making wills

- Giveaway important possessions or items

- Eat or sleep significantly more or less

- Increased substance use

Source: Adapted from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

B. Suicide Risk Assessment

If you suspect that someone is at risk for suicide, it is important to ask them directly if they are experiencing suicidal ideation or are planning to attempt suicide.

Note that asking about suicidal ideation or self-harm does not trigger either. In fact, it opens up a conversation where the person feels heard.

The WHO’s protocol for self harm/suicide involves carefully assessing the person’s thoughts, plans, and actual acts of harm, after which their emotional distress should be addressed:

- Has the person attempted suicide or done a medically serious act of self-harm? (Warning signs include signs of poisoning, bleeding from a self-inflicted wound, loss of consciousness, and extreme lethargy.)

- If so, that person must be brought immediately to a health facility. They must not be left alone.

- Does the person seem distressed or extremely agitated?

- If yes, ask if they are having thoughts or plans of suicide. Persons with active suicidal ideation, or concrete plans for taking their own life, are at greater risk for suicide. This must be attended to by removing all means of suicide from their environment like sharp objects, lethal substances, and prescription medicines.

- If no, ask if they have experienced suicidal ideation in the past month or self-harm in the past year. Persons with a history of suicidal ideation are still at risk and need active psychosocial support and professional help.

C. Psychological First Aid for Suicide

In all these levels of risk, your support could be someone’s lifeline. First, listen with empathy when a person opens up about suicide and their emotional struggles. Since a suicide attempt can be triggered by a recent distressing issue, help the person explore reasons for living and recall past instances when they were able to overcome similar problems. Second, help them connect with trusted family members, friends, colleagues who can be physically present to provide active support. Finally, remember your role as their friend, not counselor. Help them connect with a mental health professional, who will provide the appropriate medications and therapy for their distress.

D. Follow Up

The risk of repeating a suicide attempt remains high for the first 6 months, but maintaining active contact decreases this risk by reinforcing the person’s sense of connectedness and social support (Inagaki et al., 2019). For the first 2 months following a suicidal attempt or active suicidal ideation, check up on the person on a daily or weekly basis. Home visits, letters, even a quick phone call can serve as a buffer against suicidal ideation, supporting their healing and recovery.

Source: Adapted from the mhGAP Intervention Guide – Version 2.0 (WHO, 2019)

Call to action

Suicide remains a public health concern, requiring an intersectoral approach to prevention. CHD/CPRH(?) makes the following calls to optimize the country’s suicide prevention strategy:

- The Department of Health must provide an adequate budget for mental health services, expanding the accessibility and availability of mental health support, and to finally address the ongoing lack of qualified specialists.

- National laws and policy making should be focused on prioritizing community-based, evidence-informed programs that are culturally and linguistically adapted, to better guide Filipinos in their mental health journeys.

- For the media, state services, and any other authority in avoiding romanticism tied to resilience, instead, encouraging meaningful, real-world support of help-seeking and mental health awareness.

REFERENCES:

Acoba, E. F. (2024). Social support and mental health: the mediating role of perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1330720

Alibudbud, R. (2023). Towards transforming the mental health services of the Philippines. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, 39. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanwpc/article/PIIS2666-6065(23)00253-5/fulltext

Bollettino, V., Foo, C. Y. S., Stoddard, H., Daza, M., Sison, A. C., Teng-Calleja, M., & Vinck, P. (2023). COVID-19-related mental health challenges and opportunities perceived by mental health providers in the Philippines. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 84, 103578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103578

Canadian Association For Suicide Prevention. (2024, March 26). Vocabulary – How to Talk about Suicide – Canadian Association For Suicide Prevention. Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. https://suicideprevention.ca/resource/vocabulary-how-to-talk-about-suicide/

Carandang, R. R., Shibanuma, A., Kiriya, J., Vardeleon, K. R., Asis, E., Murayama, H., & Jimba, M. (2020). Effectiveness of peer counseling, social engagement, and combination interventions in improving depressive symptoms of community-dwelling Filipino senior citizens. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0230770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230770

Clapano, J. R., & Emmanuel Tupas, E. (2025). PNP logs 2,000 suicide cases. Philstar.com. https://www.philstar.com/nation/2025/07/29/2461507/pnp-logs-2000-suicide-cases

Dahildahil, R. (2023). #HelpIsWhere: Getting mental health care in the Philippines. Philstar Life. https://philstarlife.com/news-and-views/216478-helpiswhere-getting-mental-health-care-philippines?page=3

Department of Health. (2019). DOH issues guidelines on suicide prevention, joins WHO, Australia in the call for responsible media representation of mental health issues [Press release]. https://doh.gov.ph/press-release/DOH-ISSUES-GUIDELINES-ON-SUICIDE-PREVENTION-JOINS-WHO-AUSTRALIA-IN-THE-CALL-FOR-RESPONSIBLE-MEDIA-REPRESENTATION-OF-MENTAL-HEALTH-ISSUES/

Gallagher, K., Phillips, G., Corcoran, P., Platt, S., McClelland, H., Driscoll, M. O., & Griffin, E. (2025). The social determinants of suicide: an umbrella review. PubMed. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxaf004

Inagaki, M., Kawashima, Y., Yonemoto, N., & Yamada, M. (2019). Active contact and follow-up interventions to prevent repeat suicide attempts during high-risk periods among patients admitted to emergency departments for suicidal behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2017-7

Matalam, C. L., & Hembra, M. S. (2022). Community-based mental health project in Davao Region. SPMC Journal of Health Care Services, 8(2), 5. https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs64m8mb

Sinyor, M. (n.d.). CREATING AN EFFECTIVE SUICIDE PREVENTION AWARENESS CAMPAIGN. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Retrieved September 26, 2025, from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2020-01/roh_safe_activities_eng.pdf

Taliana, L. (2023). The role of community engagement in promoting mental wellness. Interdisciplinary Journal Papier Human Review, 4(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.47667/ijphr.v4i2.267

United Nations Development Programme. (2021). Prevention and management of mental health conditions in the Philippines: The case for investment. https://www.undp.org/philippines/publications/prevention-and-management-mental-health-conditions-philippines-case-investment

World Health Organization. (2016). mhGAP Intervention Guide Version 2.0. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549790

World Health Organization. (2016). LIVE LIFE: An implementation guide for suicide prevention in countries. https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/8f4bb596-e6e4-4328-a5ed-00e01ec0068d/content

World Health Organization (WHO). (2025). Suicide. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

Zuniga, Y., Dahildahil, R., Mina, J., Libanan, A., Mojica, R., Laude, K., Galindo, C., Eloriaga, M., & Labordo, E. (2020). #USAPTAYO: Utilizing TweetChat for mental health advocacy in the Philippines. European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement_5). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.706